The Monticello flower garden is composed of two elements: the twenty oval beds immediately around the house and the winding flower border that defines the West Lawn. Although there were earlier references to the flower "borders," it was not until 1807, when Thomas Jefferson began to anticipate his retirement from the presidency, that the flower gardens began to assume their ultimate shape. He then sketched a plan for the twenty oval-shaped flower beds in the four corners or "angles" of the house. Each bed was planted with a different flower, and most of the seeds and bulbs had been forwarded by Bernard McMahon, a Philadelphia nurseryman, author of The American Gardener's Calendar, and in many ways, Jefferson's gardening mentor.

The Oval Flower Beds

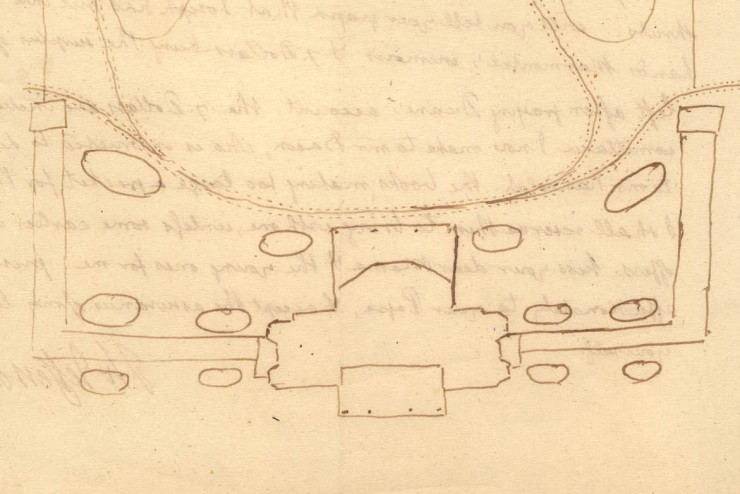

Detail from an 1807 sketch by Jefferson of the garden around the main house on the back of a letter to his granddaughter Anne Cary Randolph (Bankhead).

Oval Flower Bed with tulips in early spring next to Monticello's East Portico.

Each oval flower bed is often planted with a variety of flowers in the spring and summer.

Although there were later notations concerning plantings in the oval beds in Jefferson's garden book, a remarkable diary detailing a lifetime of horticulture at Monticello, the 1807 plan was the most complete.3 The diversity of flower species represents the scope of his interests. Many of the flowers had been grown for centuries in Europe and were commonly cultivated in early American gardens, such as roses, Sweet William, and the double white-flowering poppy. Others were curiosities, such as the winter cherry, with its lantern-like fruits, and the blackberry lily.

One bed was planted with twinleaf (Jeffersonia diphylla, shown at right), a rare, woodland wildflower that was named in Jefferson's honor in 1792 by Benjamin Barton, a noted early American botanist. Barton's tribute was inspired by Jefferson's "knowledge of natural history ... especially in botany and zoology [which] is equalled by that of few persons in the United-States."4 Other North American natives planted in 1807 included the "Columbian lily" (Fritillaria pudica), collected by the Jefferson-sponsored Lewis and Clark expedition, and the cardinal flower, which could have been found along the Rivanna River at the base of Monticello mountain. Twenty-five percent of the flowers cultivated at Monticello were North American natives, and the gardens became, in part, a museum of New World botanical curiosities.

Tulips, hyacinths, and anemones were among the flowering bulbs planted in 1807. Perhaps because they were so easily shipped long distances, bulbs played a significant role at Monticello. The tulip, for example, was the most commonly mentioned flower in Jefferson's garden book. Many of these bulbs were "florist's flowers," species highly refined through selective breeding by skilled European plantsmen.