Despite extensive research over many years, the present whereabouts of Jefferson's original Native American collections are unknown today. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, in collaboration with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, has turned this mystery into an opportunity to involve Native Americans in a contemporary arts project. Indian artists preserving traditional media were commissioned to create new pieces for the Indian Hall exhibition, based on primary source documentation of the room and study of surviving historical objects, most notably the Lewis and Clark collection at the Peabody Museum, which facilitated the artists’ examination of these important pieces. The artists involved in the project were Mary Elk (Mandan-Hidatsa), Dennis Fox (Mandan-Hidatsa), Mark McBride (Blackfeet), JoEsther Parshall (Cheyenne River Lakota), Joel Queen (Cherokee), and Butch Thunder Hawk (Hunkpapa Lakota).

Despite extensive research over many years, the present whereabouts of Jefferson's original Native American collections are unknown today. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, in collaboration with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, has turned this mystery into an opportunity to involve Native Americans in a contemporary arts project. Indian artists preserving traditional media were commissioned to create new pieces for the Indian Hall exhibition, based on primary source documentation of the room and study of surviving historical objects, most notably the Lewis and Clark collection at the Peabody Museum, which facilitated the artists’ examination of these important pieces. The artists involved in the project were Mary Elk (Mandan-Hidatsa), Dennis Fox (Mandan-Hidatsa), Mark McBride (Blackfeet), JoEsther Parshall (Cheyenne River Lakota), Joel Queen (Cherokee), and Butch Thunder Hawk (Hunkpapa Lakota).

Recreated Native American Artifacts

Native American Pipe Stem and Bowl (#2)

Native American Pipe Stem and Bowl (#1)

Native American Shield with Bear Motif

Native American Shield (with geometric forms)

Native American Shield with bird motif

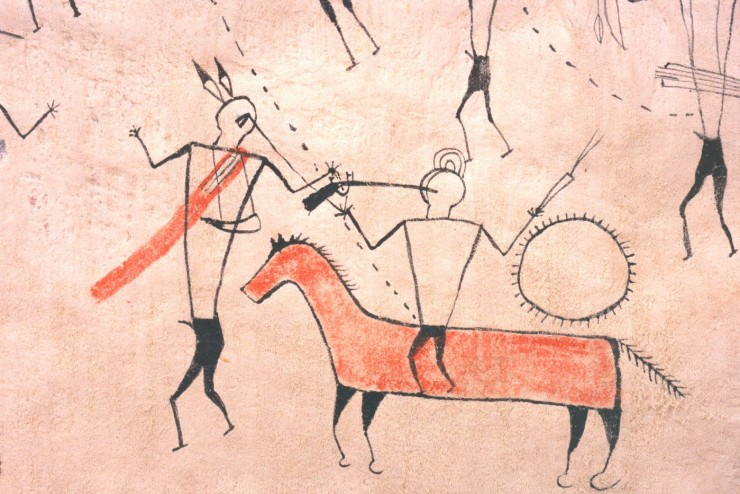

Buffalo Robe Painted with Pictographic Battle Scene

Detail of Pictographic Buffalo Robe

Native American Pipe Tomahawk

Native American Gunstock Club

Native American War Club (#1)

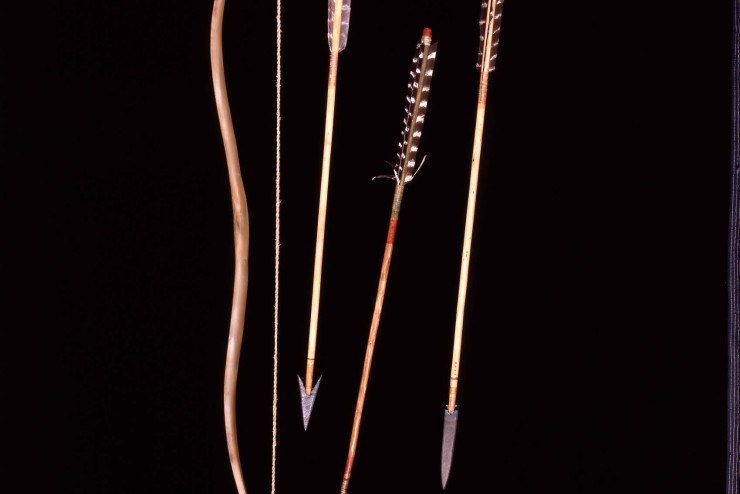

Native American Bow and Arrows

Native American Lance (#2)

Native American War Club (#1)

Vignette of various objects from the Recreated Indian Hall at Monticello

Detail of Shield, Arrows, and Club Heads

Detail of Leggings with Quill Work

Weaponry

Visitors to Jefferson's Indian Hall reported seeing "offensive and defensive weapons" among the Indian collections. Clubs with wooden handles and heads made from stones or horns were traditional weapons on the Northern Plains. They later became important ceremonial objects as other types of weapons, such as bows, arrows, lances, and clubs with metal blades became more common. Clubs at the time of the Expedition were decorated simply with feathers and horsehair. Round shields made from the thick hide of a buffalo's hump were painted with stylized symbols derived from dreams or visions that protected warriors in battle. An honored warrior would decorate a shield with eagle feathers representing great deeds of bravery.

Hide Painting

The art of hide painting is used to create the painted hide robes that were traditionally a common garment for the native men and woman of the Great Plains. Painted robes also became customary diplomatic gifts and articles of trade. Robes could contain figurative or abstract designs. Men's robes often contained representations of battles in which they had distinguished themselves. Lewis and Clark recorded receiving a robe from the Mandan chief Black Cat. The Ft. Mandan shipment to Jefferson contained seven buffalo robes, including the battle robe that he sent to Monticello. This robe depicted a conflict in which the Mandan and their Hidatsa allies fought the Sioux and the Arikara. To make a painted robe, a buffalo, elk, deer, cow, or horse hide was stretched, scraped, and tanned in a solution containing the animal's brain. After being tanned, the surface to be painted was stretched further to render it smooth and flat. Natural pigments were mixed with water and a hide glue binding agent and applied with a porous buffalo bone.

Pipes

The ritual use of tobacco was central to Native American life. On the American frontier pipe ceremonies became a means through which peaceful intentions were expressed. Pipes and smoking played an important role in the diplomatic encounters Lewis and Clark had with native people along the trail. Clark described the ritual of smoking as "the greatest mark of friendship and attention." Pipes were also important diplomatic gifts symbolizing the relationships that smoking together cemented. A pipe consists of a long hollow wooden stem sometimes decorated with eagle feathers, horsehair, or quillwork, and a separate carved stone bowl that held the tobacco. Jefferson sent two pipes to Monticello in March 1806.

Quillwork

Traditionally practiced by Native women in the Eastern Woodlands, Great Lakes and Plains regions, quillworking is an intricate form of embroidery that employs dyed porcupine quills that are wrapped, plaited, sewn, and woven using a wide range of techniques. Quillwork is used to embellish many different types of clothing and domestic and ceremonial objects, including leggings, moccasins, shirts, dresses, buffalo robes, bags, knife sheaths, baskets, baby cradles, wooden handles, tipis and pipe stems. On the Northern Plains a young woman must earn the right to do quillwork within a quillwork society by offering gifts to an elder woman in exchange for instruction in the techniques and rituals. Through quillwork societies the art has been guarded, preserved, and passed down through the generations; it survives today in many contemporary forms.